It’s an unseasonably mild winter just about verging on spring in New York City and there’s something in the air.

POTUS tells us it has come from the ever nebulous “over there”—a foreign land that is—and that it’s nothing to worry about. Bagatelle brunch must go on.

China started it, apparently, with nefarious designs, he says. Here he is now, coming to us live from behind the navy-blue lectern emblazoned with the Seal of the President of the United States, his arms flailing, lips puckered, ready to delegate, deflect, disseminate disinformation.

***

The eminently quotable although only ever mildly revolutionary, Karl Marx, once complained that “philosophers have only interpreted the world…the point, however, is to change it.”

Way back when in the late 1950s—a lifetime ago before the internet upended most everything—a young man named Donald was trying to make a name for himself in Manhattan. He wasn’t a philosopher, at least yet, but in short order he was going to both interpret and change the world.

He came from humble, but salt-of-the earth means, which is to say he was reared to adhere to mid-western sentiments and the most noble of Americana aspirations—stable income, family, two-car garage. His father had wanted him to join a staple profession of the American upper-middle class, to be a doctor or a lawyer perhaps—his mother just wanted him to be happy.

But like most young and impressionable men whose fathers have attempted to hand down to them an inalterable life trajectory, Donald followed his mother’s advice and sought the pursuit of happiness. This meant putting on hold the “serious” study of staid professionalism and moving from middle-America to middle-Manhattan.

At this point, you’ve done well to determine that the Donald in this story is not in fact as of mid-March 2020 the current President, but rather a lesser-known Donald with a similarly short last name—Judd.

While Judd was settling in Manhattan in 1960, Trump was fourteen and still probably sequestered in Queens, begrudgingly, just beginning, unfortunately, to enter puberty, to swap his gilded childhood playthings for grown-up playthings that of course to him would have meant girls—tail, pussy, etcetera.

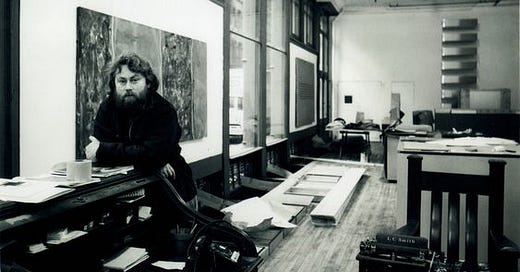

Judd, meanwhile, was freshly enrolled at Columbia arts school, learning to draw in the classical style and developing his aesthetic appreciation for the world. It was tough. He was living the starving artist’s dream, working downtown in a Soho factory keeping books by day and riding the subway all the way up to the upper West side to enter a completely different world by night. At the time, there was obviously a fully-fledged arts scene in the City, of which he was largely a peripheral figure. The scene cut across the purposefully loosely defined “arts” giving license to writers, poets, dancers, sculptors, vagrants and Abstract Expressionists alike to gather in the watering holes of downtown—places like XX—to propound novel ways of thinking, to question the foundations of mid-century American life, to drink themselves blind.

That wasn’t for Judd that speed, a tad too fast and non-thinking.

He soon settled in an apartment in Chelsea, and resolved himself to make a living through making art. The only issue was that he wasn’t very good. His early oeuvre was a mishmash of half-hearted paintings which towed the line between the abstract expressionist vogue and Malevich-esque constructivism—harsh diagonal lines intersecting planes of cloudy color.

Judd’s inability to develop a singular aesthetic derived from the fact that he wasn’t really an artist bur rather more of a theorist. A draughtsman of middling ability, he found fertile ground for artistic exploration more in the contrarian work of Duchamp than the dogma of classical beauty found in the likes of Caravaggio. For Judd, the idea in art was of chief importance, the medium of realization simply a means to an end.

So, the painting went on for a short period before he managed to liberate himself from the plane of painting and to realize that his salvation as an artist lay not in the second dimension but in the third—sculpture—although he would never call it that.

He started making his “specific objects” in the early 1960s, boxes of varying sizes that seemed impenetrable to the artistic cognoscenti of Manhattan at the time. Judd’s work was variously derided as “primitive” and “basic” but he found a patron in Leo Castelli, the proprietor of a famed downtown gallery that was willing to take a chance on young artists dedicated to upending the status quo.

The other, younger Donald was in a different place at the time, now sometime around the late 60s early 70s, but was probably more dedicated to extending the status quo, protecting it even, because it just so happened to work out in his favor more often than not. Instead of launching barbed yet incisive critiques of the contemporary art world, the younger Donald was probably enraptured in the bosom of bosoms, his life motto probably something too inane to repeat.

Judd, meanwhile, and across the rest of his too-short life, was working on inaugurating more than just a movement in the long history of art.

He would invent a belief system which he both worked and live by. Be empirical. Examine the world. Learn from the masters, but don’t be afraid to break their most sacred rules. A canvas does not necessarily hang on a wall. Painting is boring and probably irrelevant. Live within your means. Be honest with your intentions. Don’t be afraid to make things that last. Be uncompromising in the precision of your work. Take on big ideas. Ignore little people who have a fixed vision of the world, the way it should work, the way it should look.

***

Back behind the navy-blue podium and POTUS is still fiddling with the mic with characteristic vigor. Is this thing on?

He’s waxing unpoetic again, covering xenophobia, butchering the basic tenets of germ theory.

It’s still an unseasonably mild winter verging on spring in New York City and there’s still something in the air.